The countryside of Norfolk abounds with remnants

of rock dotted in fields and on the edge of towns. Ruins of castles, priories,

towers and churches, intact or crumbled into the earth; there is a wealth of

historic remains from the past centuries. Norfolk is an unlikely county to turn

to when one thinks of ancient history, i.e. BCE, but researching this era, I

was surprised at how much has been discovered. Sites and finds have been ‘waiting’

in the soil beneath our feet for thousands of years and if there are any budding

archaeologists out there (or like me, simply have a fascination with who has

walked the same tracks as us throughout history) then here are the five places

to visit in Norfolk.

Seahenge at Holme-next-the-Sea

If I had been writing about this 20 years ago, no one would have known what I was talking about. The discovery of the site was a nationwide phenomenon, not least for its mysterious meaning and the controversy around the excavation. Although its existence was known locally for decades before, 'Seahenge' (as it was dubbed by the media as it resembles Stonehenge in Wiltshire) only first came to light in 1998.

The ring of 55 small split oak trunks, thought to be 4000 years old, with in their centre a large inverted oak stump was revealed by the shifting sands to John Lorimer, an amateur archaeologist on Holme beach. Lorimer had previously found a Bronze Age axe head there and had been monitoring the site for several months when it became clear to him that something extraordinary was being uncovered. He contacted Norwich Castle Museum which eventually led to English Heritage funding the excavation of all 55 stumps amid a media storm of controversy.

Seahenge was originally built on a salt marsh, circa 2049BCE. Protected from the sea, the landscape and environment ever-changing around it; salt marsh and woodland changing to freshwater marsh, where alders and rushes produced a dark peat which preserved the timbers and kept them from decay.

It is still unknown as to why the ring was built and what it was used for. There is a theory that it was used for the laying out of a deceased body of someone important within the community.

Personally, I love the image of the ring of how it would have looked both inside and out.

The bark stripped from the inside of the posts but left on the outside would have resembled a large oak tree from afar, and then inside, the sacred feel of the pale wood. Although there is none of the original ring left on Holme beach, it can be visited at Lynn museum in Kings Lynn.

Warham Camp

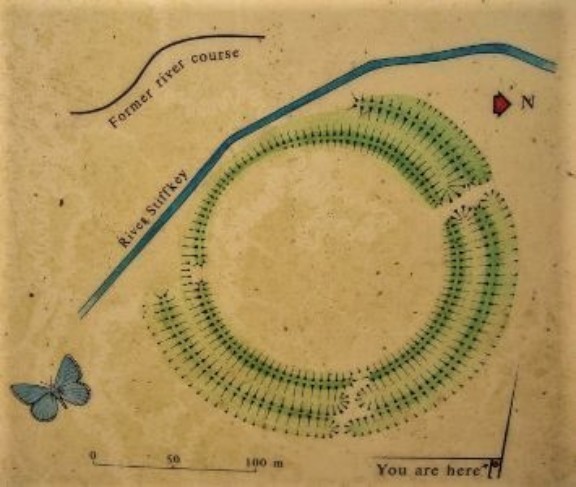

This site is very much worth a visit, not least

for the spectacular earthworks of a

three metre high double bank which gives the landscape a dramatic feel (photo below is by Hamish Fenton). Inland

from Wells-Next-The-Sea and just south of Warham village you will discover the

circular banks that are the remains of

an Iron Age fort which dates to the centuries before the Roman invasion of

Britain.

Although once completely circular, there are

banks and ditches which have been cut into by the river Stiffkey. There have

been excavations which have turned up evidence of a timber palisade and

platform at the back, and a timber retaining wall which was built to prevent erosion.

Iron Age and Roman pottery shards have been discovered between 1914 to present day.

A modern anomaly is the sight of a Holm Oak or Holly Oak which is a Mediterranean evergreen, perhaps grown by a seed dropped by birds or human, but the nearest examples would be in Holkham several miles away. There are profusions of cowslips in spring and it is a fantastic place to explore with children. Warham Camp is accessible by a footpath just off the road out of Warham.

Grimes Graves

From the smaller sites to the huge, Grimes

Graves is a large Neolithic Flint mining

complex, eight kilometres North East of Brandon near Thetford. It is the only Neolithic flint mine which is open

to the public in Britain. Originally dubbed 'Grims Graves' by the Anglo-Saxons

and it was not until the 400 pits were excavated in 1870 that they were found

to be flint mines which were dug over 5,000 years ago.

The mine was worked between 3000 and 1900 BCE although it is thought that production still

continued well into the Bronze and Iron Ages. Flint was much in demand for

making stone axe heads and even when flint had been replaced by metal, flint

nodules (small irregular rounded lumps) were in demand for uses in buildings

and as strikers for muskets.

The site stretches over an area of 91 acres and consists of 433 shafts

which have been dug into the chalky landscape to reach the flint below,

described as a 'lunar landscape' the

sight really does look other-worldly. The miners sometimes dug shafts up to 13 metres deep to where the best rocks

lay, using picks made from antlers to prise out the flint.

Today

visitors can descend 9 metres into an excavated

shaft to see the galleries and marks left by the picks of minors all those many

thousands of years ago, a fascinating and unforgettable experience (image courtesy of English Heritage).

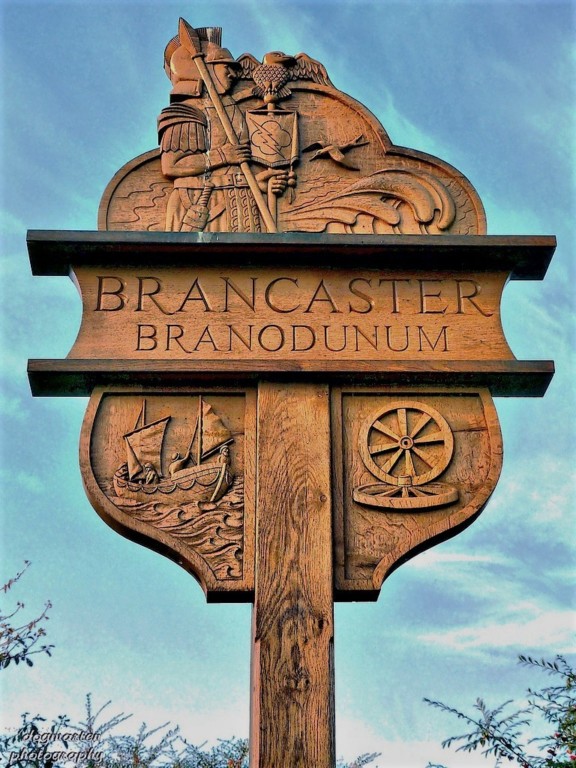

Branodunum - Brancaster

Branodunum was the name of a Roman fort which was built to the east of Brancaster on Norfolk's North coast. It was thought to be built in 2nd century (around 230) to protect against the Wash approaches, but then to control shipping and trade around the coast. Later it served to protect against invaders from across the North Sea.

It was one of a line of eleven forts between Brancaster, The Wash and Portchester in Hampshire, the name 'Branodunum' may mean 'Fort of the crow’ (or raven). Archaeological finds have included a ring, Roman-Saxon pottery, metal works and coins.

Channel 4’s Time Team made an exciting excavation in 2013. The team's geophysics workers were put to the test and it now has the largest ever range they'd ever recorded from a Roman site. As a result of the excavation several previously unknown buildings inside the fort were discovered including barracks, granaries and a possible arena for training horses.

There is also possible evidence of later Saxon use. The site of the fort is now within a field and there has been no development to cover it.

It is surrounded by the modern

village of Brancaster, so although there is not much to see, it's well worth

going there for a picnic or a walk and the National Trust signs provide lots of

information about the fort and its history. There is free access from the

adjoining A149 road or the Norfolk Coastal Walk.

Venta Icenorum at Caistor St Edmund

This list would not have been complete without a

mention of the Iceni tribe and the

name Venta Icenorum literally means

'market place of the Iceni'. Caistor had an important role as it was the

Roman base for the area of Norfolk, northern Suffolk and east Cambridgeshire.

The Iceni were a Brittonic tribe of eastern

Britain during the Iron Age and early Roman times. After the Roman invasion in

AD43, there was increasing influence on the Iceni which led to a revolt, they

were led by the deceased King Prasutagus's wife, Boudica from 60-61 AD.

Boudica was described by Roman historian Cassius Dio; 'in stature she was very tall, in appearance most terrifying, in the glance of her eye most fierce and her voice was harsh, a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips'.

Boudica's uprising endangered Roman rule so much that it resulted in the Romans burning of Londinium and other major cities (source: Wikipedia).

Even when Venta was first founded, the surrounding area was already rich in prehistoric sites; the valleys made by the rivers Tas and Yare were important routes and where they meet form some famous monuments including the Arminghall Henge and a Neolithic ceremonial monument which may date back to 3000 BCE.

After the revolt of the Iceni, they were punished severely by the Romans and their land was redistributed, Venta was probably made the regional capital through part of this process. It has been the subject of many excavations and finds over the decades. Today, you can still find evidence of the ramparts, ditch and defensive walls still standing, the forum, baths and two temples have all been unearthed since the 1930s. Caistor St Edmund is four miles south of Norwich on a minor road between Norwich and Stoke Holy Cross.

The car park is on the right hand side of the road as you head south, look out for brown signs.

There are so many fascinating places to see in Norfolk so do go and explore!

...to slightly abridge a suitable quote:

"There are many things about the prehistoric which we do not yet know or understand...But it is the unknown that leads the archaeologist on". Waldo Wedel.

Article contributed by author and ‘The Village Gardener’ Fritha Waters